The Unlikely Genius of the Renaissance

Leonardo da Vinci – even his name evokes an aura of unparalleled genius. In this biography about Leonardo da Vinci we will delve deep into the life of a man whose name is synonymous with creativity. Even centuries after his death, this Renaissance figure remains an enigma, mastering multiple arts, sciences, and disciplines.

Born in a small town of Vinci, his legacy stretches far beyond the art galleries and museums that house his masterpieces. It delves into the very fabric of science, anatomy, engineering, and our understanding of the human soul. Leonardo’s life serves as a testament to the fact that fervor, curiosity, and relentless dedication can lead to profound achievements. Join me as we follow the journey through the myriad facets of his life, reliving the Renaissance spirit as we go.

Early Life and Education (1452-1472)

Leonardo da Vinci, born Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, heralded from the picturesque town of Vinci, in the Tuscan region of Italy. His birth on April 15, 1452, was to a notary named Piero and a peasant woman named Caterina. Because of the difference in social status, a marriage to Ser Piero was unthinkable and Leonardo thus carried the stigma of being illegitimate. Catarina, who had little contact with Leonardo, married a man of her own status and Leonardo’s father likewise married a girl acceptable to his family.

During these formative years, Leonardo did not have the traditional upbringing that would be expected for a boy of his status in the 15th century. His illegitimate status excluded him from receiving a formal education in the Latin classics, like many of his contemporaries. While this could have been a setback for many, it was a blessing in disguise for young Leonardo. Free from the shackles of classical education, he pursued his own interests, which led him to observe the world around him with keen eyes. This unconventional path stoked his insatiable curiosity about nature, mechanics, and art.

Growing up in Vinci, a town surrounded by rolling hills, vineyards, and olive groves, Leonardo was captivated by nature. It’s here he developed an early fascination with the world around him. He would often venture into the countryside, sketchbook in hand, drawing landscapes, plants, and waterways. These observations of nature, both big and small, laid the foundation for his future masterpieces and his intricate studies of anatomy and flight.

In this segment of the biography about Leonardo da Vinci, we will see how Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, played a pivotal role in shaping his early career.

At the age of 15, recognizing his budding talent and keen interest in art, Leonardo’s father took him to Florence. Here, he was apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio, one of the leading artists and intellectuals of the time. This period was crucial in Leonardo’s development as an artist. Under Verrocchio’s tutelage, he not only honed his skills in painting and sculpture but also immersed himself in the diverse intellectual currents of the Florentine workshop. It exposed him to a range of subjects including metallurgy, mechanics, and carpentry, further fueling his polymathic interests.

Florence in the 15th century was a cauldron of creativity and innovation. As the Renaissance movement’s epicenter, the city was bursting with new ideas in art, science, and philosophy. Being in this environment, Leonardo was exposed to the works of other brilliant minds, which profoundly influenced his own philosophies and methodologies.

One anecdote from his apprenticeship years under Verrocchio highlights both his skill and his relentless pursuit of perfection. While working on Verrocchio’s baptismal painting of “The Baptism of Christ,” young Leonardo was tasked with painting a young angel holding Jesus’ robe. His rendition was so lifelike and superior to his master’s work that, as legend has it, Verrocchio vowed never to paint again, recognizing the unmatched talent of his young protégé. Whether this is actually true we don’t know though I personally have my doubts.

Leonardo’s time in Florence wasn’t just about art and science. It was also about forming connections and understanding the intricate web of patronage that played a pivotal role in an artist’s success. He became acquainted with prominent figures of Florentine society, which would later prove beneficial in securing commissions and support for his ambitious projects.

As the years in his apprenticeship came to a close, Leonardo was becoming a master in his own right. His reputation as a brilliant artist, combined with his insatiable curiosity, set him on a path that would see him transcend the boundaries of art, blending it seamlessly with science, and leaving an indelible mark on the world.

By the age of 20, Leonardo had qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine. This qualification not only cemented his status as an established artist but also set the stage for his subsequent explorations, experiments, and masterpieces.

In conclusion, Leonardo’s early years were a blend of nature’s inspiration, hands-on education, and exposure to the vibrant culture of Renaissance Florence. It was this unique melting pot of experiences that set the stage for the genius to bloom, promising a legacy that would forever change the way we perceive art and science.

Florence: Emergence of a Maestro (1472-1482)

Having solidified his reputation as a talented artist under Verrocchio’s guidance, Leonardo’s journey in Florence from 1472 to 1482 is a testament to his growing prowess, ambition, and the formation of his distinctive style.

By the time Leonardo qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke in 1472, Florence was flourishing as the epicenter of the Italian Renaissance. The city teemed with artists, thinkers, and merchants, becoming a nexus of intellectual discourse, artistic rivalry, and innovation. While the guild membership gave him the professional autonomy he needed, it was this stimulating environment of Florence that truly galvanized his creativity.

One of the first records of Leonardo’s independent work was in 1473, with the drawing of the “Arno Valley.” It stands as testament to his continuous fascination with nature and his evolving expertise in depicting landscapes. You can see the drawing below.

In this period, Leonardo started to garner commissions on his own, moving out of Verrocchio’s shadow. His work on “The Annunciation” showcases not just his supreme skill in capturing human forms but also his ability to integrate those forms into a harmonious, spatially coherent landscape setting. It is a symphony of divine narrative and nature, intertwined in perfect harmony.

While Leonardo’s artistic ventures flourished, his notebooks from this period reveal that his insatiable curiosity extended far beyond paint and canvas. These journals are scattered with observations of river currents, sketches of Florentine buildings, detailed anatomical drawings, and myriad inventions. They bear witness to a mind that constantly observed, dissected, and sought to understand the very essence of the world around him.

If you would like to page through some of these note books you can go HERE.

In the vibrant streets of Florence, Leonardo would have crossed paths with other luminaries of the time, including Botticelli and Ghirlandaio. This period was rife with artistic competitions, pushing every artist to outdo one another. While there’s no direct record of a rivalry, the competitive spirit of the times undoubtedly spurred Leonardo to reach greater heights.

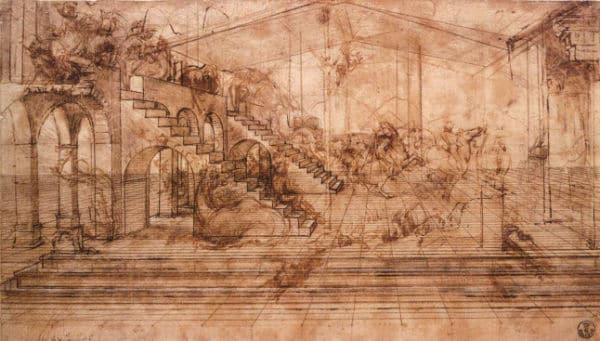

A significant testament to Leonardo’s growing reputation was the commission of the “Adoration of the Magi” in 1481 for the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopeto.

Leonardo’s approach was evident – building on but departing from tradition in places. The movement of the crowd admiring the Virgin and Child is clear and was a lesson he learned from his teacher. He breaks from tradition in placing the Virgin and Child in the centre of the piece. Traditionally the focus of the painting would have been placed on the side, approached by the kings from the opposite side.

He makes use of linear perspective (size diminishing with distance), which was widely used at the time, but also introduced perspective using diminishing detail (objects further away have less detail) and changes in intensity (objects further away are more muted). These were new concepts he had observed and recorded in his notebooks.

The unfinished work provides a glimpse into Leonardo’s meticulous planning process. More than just an art piece, it was a study of movement, expression, and chaos, with intricate groupings and dramatic gestures. The work’s dynamism and depth give us a hint of the monumental shifts Leonardo was bringing to the art world.

Outside of his artwork, the Florence years were also pivotal in shaping Leonardo’s character and worldview. Immersed in a culture that valued knowledge and patronage, he understood the importance of aligning with influential figures. It’s during this time that he began seeking the patronage of the Medici family, the de facto rulers of Florence, who were known for their support of arts and sciences. While there isn’t direct evidence of a formal relationship, Leonardo’s presence in their circles certainly expanded his horizons and connections.

The culmination of his Florentine years is best exemplified by the “Benois Madonna,” an artwork that showcases Leonardo’s evolving style. In it, we see the tender interaction between Mother and Child, the soft sfumato technique that became synonymous with Leonardo, and a landscape that stretches infinitely, capturing his love for nature and depth.

However, as the decade drew to a close, the winds of change beckoned. Leonardo’s growing ambitions and perhaps the allure of new challenges and patrons led him to leave Florence for Milan in 1482. But his years in Florence had already set the stage. He departed not just as an accomplished artist but as a polymath, poised to transform every field he would touch.

In retrospect, the decade between 1472-1482 wasn’t just about Leonardo’s growth as an artist. It was about the emergence of a maestro who would redefine art, intertwining it with science, nature, and emotion in a manner never seen before. Florence was the crucible, and out of its fiery depths of creativity and competition, Leonardo emerged, phoenix-like, ready to soar to even greater heights.

Journey to Milan (1482-1499)

As this biography about Leonardo da Vinci unfolds, we see his journey to Milan marking a significant shift in his artistic and scientific pursuits.

By the time Leonardo reached Milan in 1482, he was more than just an artist; he was a multifaceted genius poised to enthrall a new city with his talents. The motivations behind this significant move are myriad. Whether it was the allure of the illustrious Sforza court, the desire for greater challenges, or simply the intrinsic need to expand his horizons, Milan became Leonardo’s playground for nearly two decades.

Upon arriving, Leonardo wasted no time in introducing himself to Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. It wasn’t just his painting skills that Leonardo highlighted to the Duke, but his prowess in engineering, architecture, and military strategy. The Milanese court, rich and receptive, was the perfect setting for Leonardo’s interdisciplinary talents.

One of the initial projects Leonardo undertook was an equestrian monument in honor of Ludovico’s father, Francesco Sforza. Although “The Horse” was never completed due to the complexities involved and political disruptions, Leonardo’s designs and plans for this ambitious project showcased his innovative thinking. His studies for this monument were exhaustive, delving deep into horse anatomy, dynamic poses, and metallurgical challenges.

Yet, while the grandiose equestrian statue remained unrealized, it was during this Milanese period that Leonardo would create some of his most iconic works. The “Last Supper,” commissioned for the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, is a testament to his understanding of human psychology, emotion, and his expertise in using perspective to dramatic effect. In this mural, Leonardo encapsulates a pivotal moment in Christian narrative, the instant Jesus announces a betrayer among his disciples. It remains one of the most studied and replicated artworks in history.

Milan became more than just a place of artistic commissions for Leonardo. It was where he deepened his scientific investigations. His notebooks from this period are filled with studies on hydraulics, flight, and anatomy. The Duke’s patronage granted him access to human cadavers for dissection, allowing Leonardo to create some of the most detailed and accurate anatomical drawings of his time, bridging the gap between art and science.

A remarkable example of Leonardo’s engineering ingenuity during his Milanese tenure is the design of the intricate lock system for the Martesana Canal. His innovative approach not only solved practical problems but also showcased the harmonious blend of functionality and aesthetic design.

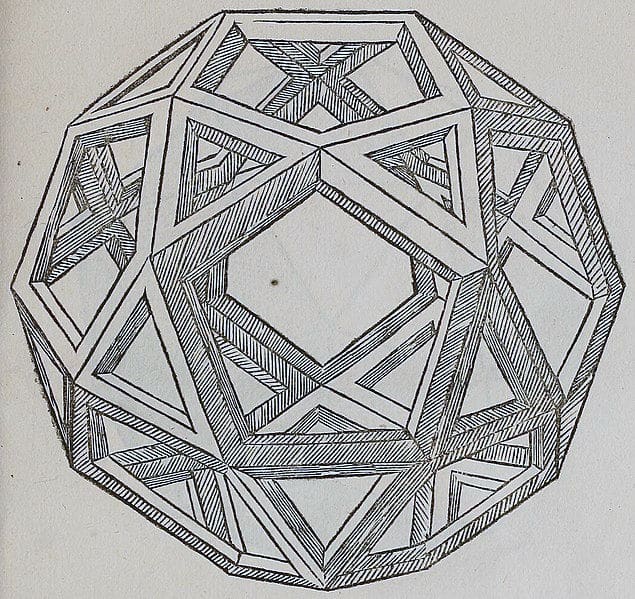

The cultural ambiance of Milan under the Sforzas was electric. Leonardo, always seeking knowledge, would have rubbed shoulders with prominent intellectuals, musicians, and artists of the time. The court was also where he met the young mathematician Luca Pacioli. Together, they delved into the mysteries of proportion, leading to the development of the “Divine Proportion” or the “Golden Ratio,” which would significantly influence Renaissance art and architecture.

Music was another realm Leonardo explored while in Milan. His designs for musical instruments, like the viola organista, showcase his desire to augment or redefine existing boundaries. It’s said that Leonardo’s musical talents were as exceptional as his artistic ones, with his performances enchanting the Milanese court.

Leonardo’s time in Milan, however, wasn’t just a period of relentless creativity and exploration. It was also a time of personal growth and relationships. His notebooks from this era often mention his pupils and assistants, the most notable being Francesco Melzi, who would become a lifelong companion. Their close bond is evident in Leonardo’s works, where Melzi often played a significant role, either as a model or as a collaborator.

By the close of the 15th century, political winds in Milan shifted with the French invasion and the fall of the Sforza dynasty. Leonardo, ever the pragmatist, sensed the changing tides. His journey in Milan had spanned almost two decades, filled with incredible achievements and a few unrealized dreams. By 1499, it was time to move on.

In retrospection, Leonardo’s Milanese chapter wasn’t just about monumental artworks; it was about a holistic evolution. He emerged as an unparalleled polymath, seamlessly merging art with science, engineering, music, and architecture. Milan was not just a backdrop but an active catalyst, nurturing and being reshaped by the genius of Leonardo da Vinci.

Back to Florence (1500-1506)

As Leonardo returned to Florence in 1500, the city was undergoing profound changes. The Republic had been re-established after the fall of the Medici dynasty, and Florence was once again a buzzing hive of artistic and intellectual activity. This was the Florence of Michelangelo and Raphael, a competitive arena of artistic genius. Leonardo, however, wasn’t returning as the young apprentice of Verrocchio; he was now the renowned master who had captivated Milan.

Leonardo’s re-entry into Florentine society was marked by personal reflections and an even deeper dive into scientific investigations. He seemed to be less interested in monumental public commissions and more consumed with private studies and smaller scale works. One might interpret this shift as Leonardo’s conscious decision to focus on projects that truly piqued his interest, rather than those dictated by patronage or societal demands.

One of his most celebrated works from this period is the “Mona Lisa.” Commissioned by Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo, this portrait of his wife, Lisa Gherardini, would become one of the most recognized and enigmatic paintings in art history. Leonardo’s use of sfumato, the soft transition between colors and tones, gives the portrait its mysterious aura. The gentle smile of Mona Lisa, the atmospheric backdrop, and the play of light and shadow showcase Leonardo’s matured artistry.

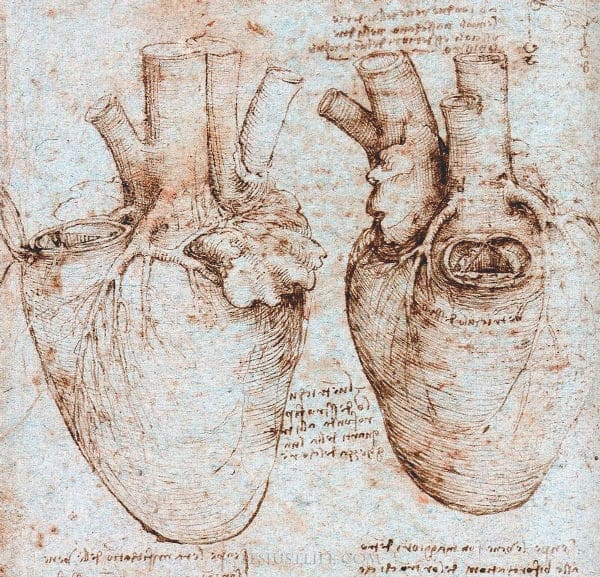

It wasn’t just the mastery over paint that occupied Leonardo in Florence. His relentless fascination with anatomy continued. His drawings became more systematic, culminating in plans for a comprehensive treatise on human anatomy. He performed dissections, not just out of artistic interest but driven by a scientific thirst to understand the human machine. One of his notable sketches from this period is the detailed study of the human heart, where he even hypothesized the function of the atrioventricular valve.

The competitive spirit of Florence during this time was palpable. Leonardo found himself amidst a fierce artistic rivalry, most notably with the young Michelangelo. Both were commissioned to paint vast battle scenes on opposite walls of the Hall of Five Hundred in the Palazzo Vecchio: Leonardo with “The Battle of Anghiari” and Michelangelo with “The Battle of Cascina.” Unfortunately, neither project was completed, but they became legendary, showcasing the contrasting styles and techniques of the two titans. Leonardo’s experimental technique for “The Battle of Anghiari” led to technical issues, causing the paint to drip. Yet, the sketches and the few remaining fragments of these works display the dynamism and intensity Leonardo intended to portray.

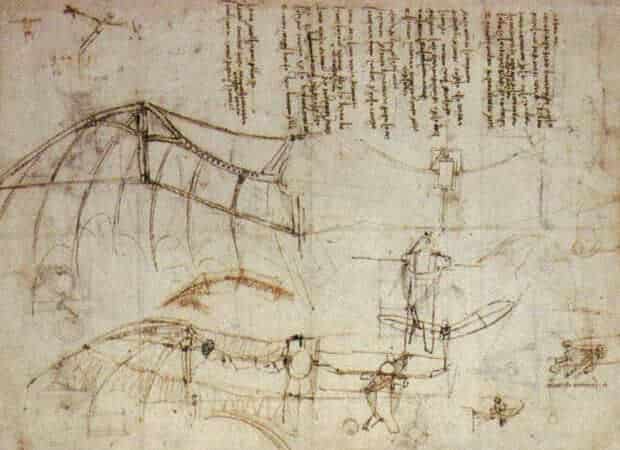

Parallel to his artistic endeavors, Leonardo’s notebooks from this period were filled with studies on botany, water flow, and flight. His designs for various flying machines, including the ornithopter and the aerial screw, were ahead of their time, demonstrating a profound understanding of aerodynamics and the principles of flight. Inspired by birds, he meticulously studied their flight mechanics, dreaming of the day humans might soar in the skies.

While in Florence, Leonardo also took on the role of an educator, training the next generation of artists. His workshop was lively, filled with students meticulously copying their master’s works and techniques. Among them, artists like Francesco Melzi and Salai stood out, not just as students but as close companions and confidantes.

Yet, despite his accomplishments and the comforts of being back in his homeland, restless curiosity drove Leonardo. Florence, for all its artistic fervor, was becoming too familiar, too insular. By 1506, the winds of change beckoned again. Leonardo’s insatiable quest for knowledge and novelty led him back to Milan, now under French rule, a move that would mark yet another significant chapter in his life’s odyssey.

In revisiting his time in Florence, one observes a Leonardo who was introspective yet relentless, an artist who was becoming increasingly fascinated with the natural world and the underlying principles that governed it. The city, with its shifting political landscapes and burgeoning artistic rivalries, provided both challenges and inspirations. Leonardo’s second Florentine chapter, while brief, was undeniably influential, setting the stage for the multifaceted explorations in the years to come.

Milan and Beyond (1506-1513)

This part of the biography about Leonardo da Vinci brings us to his return to Milan in 1506, a city transformed from the one he left. Though Ludovico Sforza no longer held power and the French reigned supreme, Milan’s admiration for Leonardo remained unwavering.

Charles d’Amboise, the French governor, swiftly became one of Leonardo’s chief patrons. It was under d’Amboise that Leonardo was honored with the title of “painter and engineer of the Duke,” reflecting his dual mastery in art and the sciences.

One striking piece from this era was “Portrait of an Unknown Woman” or “La Belle Ferronnière”. Speculated to represent Ludovico Sforza’s mistress, this painting manifested Leonardo’s evolving artistic genius, masterfully juxtaposing a detailed human portrait against a tranquil, faraway landscape.

However, the allure of science increasingly claimed Leonardo’s attention. His fascination with hydraulics prompted innovative models for water systems and ingenious solutions for canal locks.

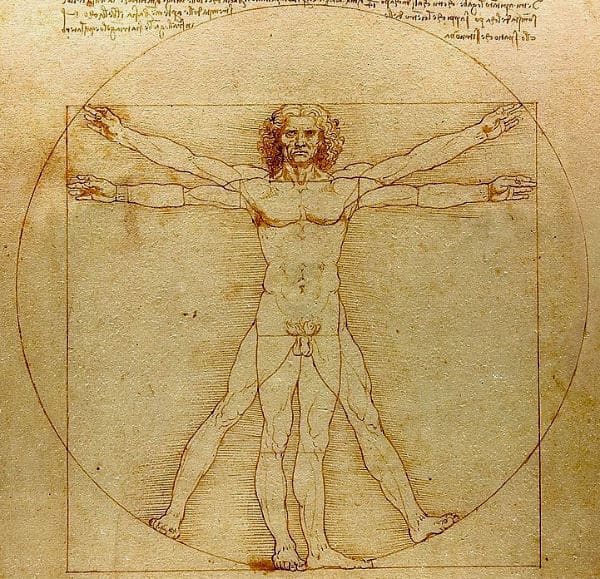

One mustn’t overlook his iconic Vitruvian Man during this period. An epitome of the Renaissance’s blend of art and science, this drawing captures Leonardo’s insight into human proportions, as described by Vitruvius. Illustrating a man harmoniously fitting within both a circle and a square, it symbolizes the interconnectedness of earthly existence and the cosmic universe.

His anatomical quests continued, strengthened by his collaboration with Marcantonio della Torre, a renowned anatomist. While their grand plan of a detailed anatomy treatise remained unrealized, Leonardo’s intricate drawings from numerous dissections set new paradigms, especially his groundbreaking studies on the human skull, eye, and fetus.

Leonardo, ever the collaborator, joined forces with polymath Francesco di Giorgio, leading to innovative architectural and engineering feats like canal constructions and fortified designs. This union of Renaissance giants gave rise to concepts far ahead of their time.

Leonardo’s dreams of flight also found deeper grounding. His Codex on the Flight of Birds illuminated his rigorous observational approach, as he meticulously documented avian-inspired flight designs and preliminary aerodynamics principles.

His retreats to the Italian countryside further fed his insatiable curiosity. Through these travels, he sketched, pondered, and reflected, documenting everything from detailed botanical studies to musings on light and shadow’s interplay in nature.

But, as the sun set on his Milanese chapter by 1513, Rome’s ancient allure and the artistic promise it held under the patronage of Giuliano de’ Medici beckoned Leonardo.

In this Milan phase, we witness a Leonardo in full stride, straddling the realms of art and science with unparalleled grace. Whether crafting enchanting portraits or penning theories lightyears ahead, his Milanese tenure stands testament to his boundless curiosity and pioneering spirit.

Rome and Final Years (1513-1519)

Because of political upheavals, Leonardo left Milan and moved to Rome in 1513 with his two studio assistants Melzi and Salai.

In Rome he was very highly regarded, but he was relatively inactive and remarkably aloof from Rome’s rich social and artistic life.

In 1515 France’s king Francis I, offered Leonardo the title of Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King and a now elderly Leonardo was given a country house at Cloux and a stipend to live off.

His new patron did not demand much of him by way of commissions. (One notable exception was a commission to produce a mechanical lion that could walk and open its belly to display a bouquet of lilies). The King was satisfied with tapping Leonardo’s vast storehouse of knowledge, which left him free to concentrate on his scientific writings.

If you are industrious you can purchase a kit and build your own Leonardo Mechanical Lion replica.

Though painting wasn’t his prime focus in Rome, he didn’t abandon it altogether. Rumors circulated of a few works he might have undertaken, but evidence is sparse. What is undeniable, however, is Leonardo’s influence. The very aura of his presence in Rome, his methodologies, and his relentless inquiry into the nuances of nature and art left an indelible impact on the artists of the time.

By 1516, a new opportunity beckoned. Leonardo was invited to the court of Francis I of France, a young monarch who revered the Italian master. Leaving Rome behind, Leonardo traveled to France, settling in the Château of Cloux, near Amboise.

This French sojourn marked a gentle, introspective phase of Leonardo’s life. While he took on fewer projects, his advisory role at the court of Francis I was a testament to the king’s respect for his genius. One of his known works from this period is the delicate “St. John the Baptist,” which showcases his mastery over the play of light and shadow.

Leonardo’s final years in France were marked by reflection and consolidation. He revisited his notebooks, organized his vast array of sketches, and documented his myriad observations. In the tranquillity of the French countryside, surrounded by pupils and admirers, Leonardo continued his studies on flight, anatomy, and various natural phenomena.

Yet, even as his health declined, Leonardo’s spirit remained unquenchable. He continued sketching, observing, and questioning until the very end. On May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, the Renaissance polymath breathed his last, leaving behind a legacy unparalleled in its breadth and depth.

In a life filled with ceaseless exploration, Leonardo da Vinci transcended the boundaries of his time, embodying the essence of the Renaissance. From the bustling studios of Florence to the courts of Milan and the ancient streets of Rome, and finally to the serene vistas of Amboise, Leonardo’s journey was not just of places but of ideas, visions, and ceaseless curiosity

Conclusion

Leonardo’s life, marked by ceaseless inquiry and innovation, underscores the boundless potential of human endeavor. His journey, from an illegitimate child in Vinci to the epitome of Renaissance brilliance, exemplifies the heights one can achieve through passion and perseverance. In Leonardo’s story, we find a testament to the idea that regardless of one’s origin or educational background, with enthusiasm and energy akin to Leonardo’s, success is possible.

If you enjoyed this biography about Leonardo da Vinci, you will enjoy reading about the colourful life of Gauguin.

Pin Me