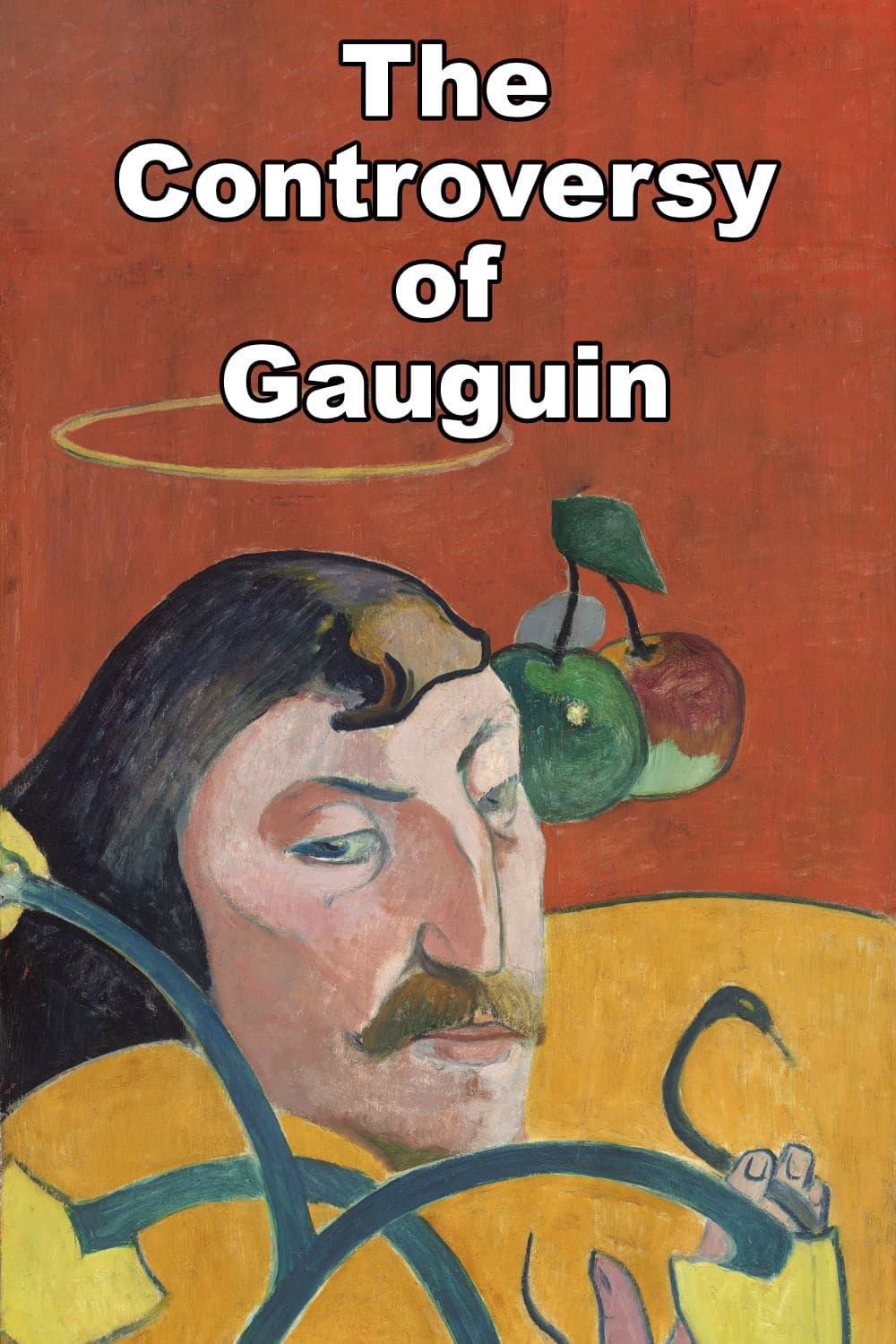

Paul Gauguin (1848 – 1903), a French Post-Impressionist artist, was and still is a controversial figure in the art world for several reasons. In this article we will take a closer look at some of these controversies. The article will help those studying Gauguin at school and those interested in the history of art.

TLDR;

Here are some key factors that contributed to his controversial status:

1. Cultural Appropriation

Gauguin’s work is often criticized for appropriating and exoticizing non-European cultures, particularly the indigenous people of Tahiti and other Pacific Islands. He portrayed these cultures through a romanticized lens, often ignoring their complexities and reducing them to stereotypes. Some argue that Gauguin’s portrayals perpetuated harmful colonial attitudes and objectified the people he depicted.

2. Personal Life

Gauguin’s personal life and lifestyle choices also added to his controversial reputation. He left his wife and children to pursue his artistic ambitions and traveled extensively, often living in poverty and with unconventional relationships. His behavior, including his relationships with younger women and his sometimes volatile personality, garnered criticism and created a negative public perception.

3. Artistic Departure

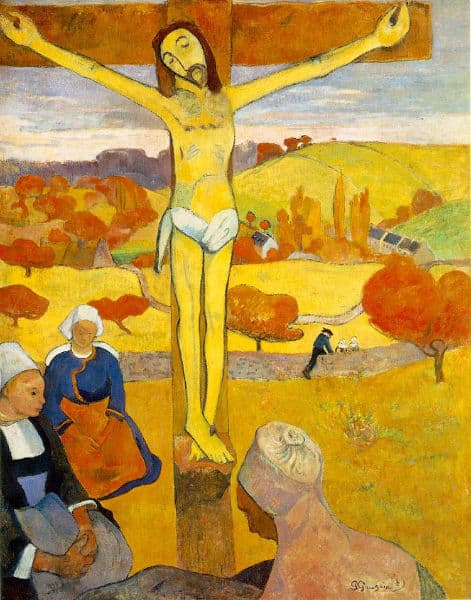

Gauguin’s departure from traditional artistic techniques and his rejection of naturalistic representation were met with resistance from the art establishment of his time. His bold use of color, flattened perspective, and distorted forms went against the prevailing artistic norms. Critics and conservative audiences found his works difficult to understand and considered them provocative or even nonsensical.

4. Sexuality and Symbolism

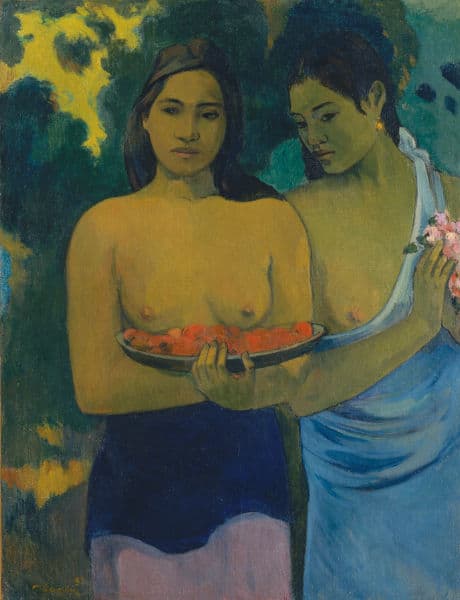

Gauguin’s artwork often explored sensual and erotic themes, including nudity and sexual imagery. His paintings, such as “Spirit of the Dead Watching” and “Nevermore,” were deemed scandalous and morally objectionable by many during his era.

5. Posthumous Controversies

The controversies surrounding Gauguin extended beyond his lifetime. After his death, his reputation faced renewed scrutiny as more information about his relationships, including his relationships with young girls in Tahiti, became known. This reevaluation further fueled the debate about his ethical conduct and its impact on his artwork.

Introduction

While Gauguin’s contributions to art and his influence on subsequent movements cannot be ignored, his controversial personal and artistic choices continue to generate discussion and debate. The examination of Gauguin’s legacy involves confronting the complex intersections of art, culture, colonialism, and ethics.

Paul Gauguin presents an area of difficulty for viewers of his work. It is impossible to look at his paintings and not feel a range of emotions. His use of bright, bold colour first catches the eye. Then one looks closer and the image becomes murkier; exoticised and often nude female bodies, passive expressions, confused cultural references. Gauguin’s work is strange and at the same time, strangely captivating.

To this day he remains a highly divisive figure. In many ways, his art is inseparable from his troubling personal life and the colonial context in which he produced it. These factors have spurred many revisionist critiques in recent decades and the controversy surrounding him continues today.

This article will consider the different sides of Gauguin, looking at his artistic achievements as well as his personal relationships. Similarly, it will explore his almost mythological status, largely built by himself, and some of the ways in which we can seek to understand his place in contemporary art history.

Entering the Art World

The story of how Gauguin came to be a painter is an interesting one. He was born in 1848 and much of his early life was spent in Peru with his family, escaping the Napoleonic revolution in Paris. Many art historians have credited this time with inspiring his later lust for travel and discovering ‘the other’ beyond Paris.

As a teenager, he joined the merchant marines and the French Navy, which took him to India and the Black Sea. When he returned to his homeland, he became a stockbroker, whilst simultaneously selling and painting impressionist works. He continued in this manner for 10 years.

This path came to an abrupt end, however, as a result of the stockmarket crash in 1882. Faced with unemployment and ruin, Gauguin turned to painting full time. In 1884, he moved to Copenhagen with his wife, who was originally from Denmark, and their five children. Just one year later, he returned to Paris alone, supposedly in an attempt to further his painting career.

Despite his varied professional story, Gauguin spent much of his life penniless. His life was one of financial struggle and displacement, experiencing semi-obscurity as an artist and long periods of destitution. To some extent this translates into his work, much of which has a darkness and melancholy, despite its audacious colour palette.

His early profession also led to many of his peers criticising him throughout his life. They critiqued his claims that his art had a higher, purer meaning, instead claiming that his motivations were purely commercial. To them, his works were nothing more than contrived and clichéd.

The idea that his stockbroker experiences had imbued him with capitalist desires is plausible, however. It is perhaps this background that led him to render Polynesia as a postcard ready destination of exotic, primitive natives. This perspective appealed to his market of Parisian elite who favoured anything that depicted the romance of the ‘other’, especially coming from newly colonised nations.

In doing so, he aligned his works with the expositions of the French government that aimed to promote their new colonial conquests. Indeed, his trip to Tahiti was inspired by an exhibition in Paris in 1889. He became determined to move there and vowed to his wife, Mette, that his return would be the start of a new beginning for their family.

Artistic Achievements

Whatever his motivations, the impact his trip to the tropics had on his work was important. His recognition today primarily comes from his compositions of brown-skinned Tahitian girls and women, many in static, dreamlike poses.

However, first and foremost, Gauguin’s artistic innovations are what stand out most. He used colours fearlessly, experimenting with a vibrant, undiluted palette that was built on contrast and extremes. In this way, he moved away from realism and the naturalistic tendencies of the impressionists, pioneering the post-impressionist style and moving towards expressionism. At the same time, he adopted a different style of brushwork and flat, decorative surfaces of colour, inspired by Japanese prints.

This radical stylistic shift began during his time in Brittany. Here he sought out an untouched, unmodernised rural lifestyle, which he began to paint in his own, novel way. It has been affirmed that it was here, rather than in the South Seas, that Gauguin’s art displays its most significant developments.

These artistic achievements had an enormous impact on his contemporaries and successive artists after them. Most notably, Picasso and Matisse drew on his use of colour and crudely drawn figures, helping both artists towards their own levels of extreme fame. As a result of these innovations, Gauguin has been credited with uttering in an entirely new and revolutionary visual vocabulary.

In many ways, his colourful abstracted work also set the stage for contemporary abstractionism. Along with Cezanne, he has been hailed as a key figure in the founding of modern art. His monumental impact on Western Art cannot be understated. However, many recent critiques have pointed out that his context within Polynesian art is slightly different and perhaps rather less radical.

He further tested his abilities working with sculpture, woodcarving, ceramics and prints, among other mediums. This hunger for experimentation stands out in his body of work and deserves recognition.

Mythological Legacy

Gauguin’s uniquely post-impressionist work was also characterised by its increasingly symbolic subject matter, which contrasted with the impressionist’s depictions of everyday objects and forms. This feature of his paintings is central to understanding Gauguin as an artist and as a man.

When he first moved to the South Pacific Islands, Gauguin went in search of a “more natural, more primitive and above all less spoiled life”. He wrote these words in a letter to Van Gogh, whom he stayed with in Arles in 1888, prior to leaving France. His initial voyage was partially funded by the French Ministry of Public Education and Fine Arts, on the understanding that he would document life in Tahiti.

His tropical fantasy was not realised when he arrived in the Tahitian capital of Papeete, however. What he found was a country already transformed as a result of French missionary movements and colonial influence. The ‘noble savage’ that he had so hoped to find was not there, nor did it exist on any of the more remote islands that he desperately sought out.

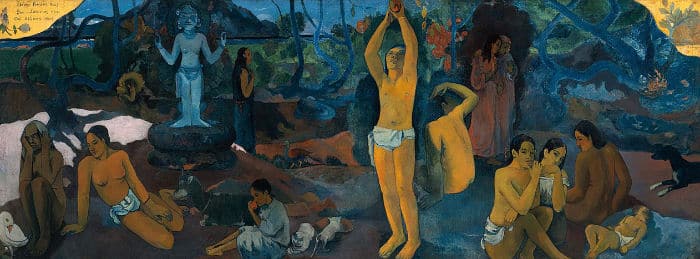

In response to this disappointment, Gauguin set about constructing his fantasy for himself. In his radically experimental art, he draws on different symbols and traditions from Europe, ancient Tahiti, Japan, Mesoamerica and much of Southeast Asia. Some of his paintings feature ‘Polynesian’ statues and totems, actually taken from photographs of Asian art that he purchased in France. Similarly, the flamboyant, romanticised fabrics that are draped across his subjects were also imported from Europe.

During this time, he wrote a travel journal of sorts to document his journey. This account is highly fictionalised. The written work perpetuates the bold myths that he depicted in his art and presents a highly eroticised image of the islanders and their mystic world that he claimed to have found. He spoke of wanting to capture ‘the music of painting’, finding the harmony between different colours in his art.

In all his works, there is a narrative element that shines through. However, they often feel incomplete, his compositions are mysteries that are never quite revealed. In this way, they echo Gauguin’s experience of Polynesia.

Personal Life

Beyond Gauguin’s work within the art world and his varied and sometimes entirely fabricated inspirations, it is necessary to consider his personal life. Whilst many have argued that the artist’s biography is irrelevant when considering his work, it is nonetheless a key factor in the controversy that still surrounds his legacy.

Many of the muses in his work were directly related to his personal life. The indigenous women he depicted were often his lovers in real life and he regularly painted his young wife, Teha’amana. This girl, who was only 13 when they married, was one of three teenage wives that Gauguin took during his time in the Pacific Islands. He is famed for creating ‘La Maison du Jouir’ for himself, translated to mean ‘the House of Orgasm’. On his return to Paris in 1893, he separated from Mitte, his first wife, and emigrated permanently in 1895.

He is known to have infected his wives, and countless other women in Tahiti, with syphilis. Complications with the venereal disease are thought to have been the cause of his death in 1903. He was 54 when he died and living on the Marquesas Islands.

The pervasiveness of critiques surrounding Gauguin’s paedophilic relationships is partly due to their presence in his art. It is impossible to ignore the indigenous, undressed women who feature in so many of his works and the sexualised, tropical fantasy he constructed to accompany them. There is an undertone of violation that surfaces, despite the mythical and abstracted nature of his art. Although he depicts the figures as innocent and naïve, the viewer is unwittingly aware of the erotic and exploitative reality. This knowledge is arguably what makes his work so charged.

At the same time, there is a sense that the artist, and viewer, is somehow removed from knowing his subjects too deeply. There is something impenetrable about their expressions. These portraits conflict with the sexualised reality that we now understand. Nonetheless, these silent female identities remain out of reach, even as they are laid bare before us.

It has been theorised that in his personal life and his professional life, Gauguin was doomed to be an outsider. In many ways, his focus on romanticising the South Seas was an attempt to deceive himself as much as his bourgeois audience.

He lived there for much of his life and never returned to France. One cannot help believing that there must have been something that led him to stay. Alternatively, perhaps his emigration was an attempt to rewrite the story of his failures and to paint himself as the martyr that he so hoped to be. Maybe his flight to the land of fantasy was really a means of escape.

Understanding Gauguin Today

Despite the questionable ethics behind Gauguin’s work, many have praised his lavish, indulgent use of colour. Some argue that his art captures an unattainable ideal that he alone was brave enough to present and this has led to him being sorely misunderstood. Similarly, he has been characterised as a loveable rascal who lived with a freedom that many can only dream of.

The tourism industry in Tahiti still promotes Gauguin’s legacy, feeding off the myth he created of a colourful, untouched paradise. Replications of his art can be seen for sale in tourist shops and has inspired the names of cruise ships and restaurants alike, all of which promote his carefully constructed image of utopia.

It was not until the late 1980s that discussions began to emerge questioning the provenance of Gauguin’s inspiration. Several works suggested that his positioning as a white, male artist in a patriarchal, imperial context was problematic. This interpretation gradually garnered more attention and analysis of the troubling stereotypes that he perpetuated and exploited are now central to modern interpretations of his work.

Similarly, Tahitian artists have responded to his art, exploring its enduring impact on the image of Tahiti and its native population. There has been a range of exhibitions that deliberately seek to draw attention to the juxtaposition between the European interpretation and the Tahitian interpretation of the islands.

In many ways, Gauguin now lies in the shadow of his former friend, Vincent Van Gogh. Certain critics have accredited this with Van Gogh’s less divisive subject matter. His depictions of sunflowers and other still life compositions have made him a commercial success, replicated thousands of times over. These uncontroversial images are more suited to mass audiences and commercialism. In contrast, Gauguin’s oeuvre is far too uncomfortable for widespread fame. Knowledge of his life prevents him from being venerated on the grand scale of many of his contemporaries.

There is no doubt that Gauguin had a significant impact on modern art and that his range of work was both impressive and ambitious. It is impossible to ignore the extreme colours and experimental forms that make it so appealing to some.

Whilst his work is captivating, however, it is hard to consider it without also acknowledging the life behind the art. Though people have questioned why Gauguin’s life is so commented upon when the biographies of other troublesome artists are often ignored, there is an indisputable controversy surrounding his art that continues to this day. In many ways, the art world still wrestles with the questions posed in his most famous work titled ‘Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?’

If you enjoyed reading this article you will also enjoy reading about the 3 Abstract Artists that Changed How We Look at Art.

Pin Me